3, 2, 1… Lift-off! A Safer Way to Ignite Amateur Rockets

⚠️ Disclaimer: This project involves high voltages (up to 400V). Mishandling can result in serious injury or death. Do not replicate this unless you understand the risks and follow strict safety precautions.

This is the story of how an optional university project led to the design of increasingly advanced rocket igniters—culminating in a compact and powerful 3.7V to 400V DC-DC Boost Converter device.

Project Motivation

The story began with an attempt to build a model rocket for an optional project in Classical Mechanics II with a couple of classmates back in 2019. The project turned out to be much harder and longer than expected, and our professor considered it somewhat risky, so we decided switch to a simpler one—a ballistic pendulum, which I’ll reserve for a future post. Switching the project didn’t mean giving up on the original idea—one of my teammates and I kept working on it way beyond that initial setback.

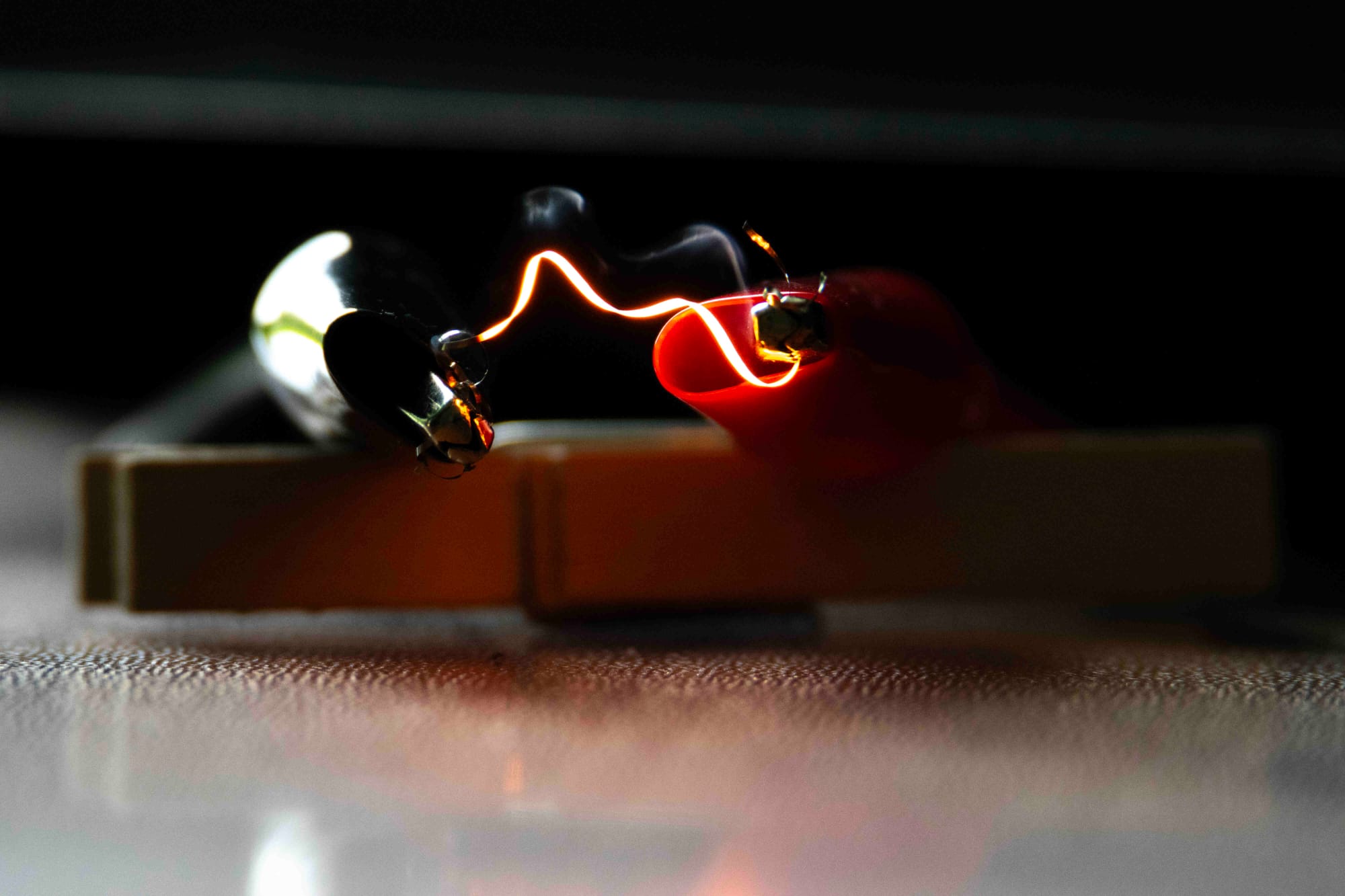

A couple of years later, despite progress in several areas, we still struggled with inconsistent ignition. Our simple igniter used—and practically was—a 9V alkaline battery to short-circuit a thin iron wire. Unfortunately, the long cable runs to the launch pad and low voltage often resulted in insufficient current to burn the filament. In other words, it didn’t always work—which made it even more dangerous. If a rocket failed to fire, we had to wait a long time before safely approaching it to check what had happened. It was frustrating, time-consuming, and risky.

In the summer of 2021, I developed a basic 18V ignition system with a conductivity check to determine whether ignition was possible. Even though it worked, I wasn’t fully satisfied with it. This was the spark (pun intended) that triggered a much deeper dive into high-voltage electronics. It would become one of our first serious electronics projects—we learned a lot and burned through lots of components along the way.

First Working DC-DC Boost Converter

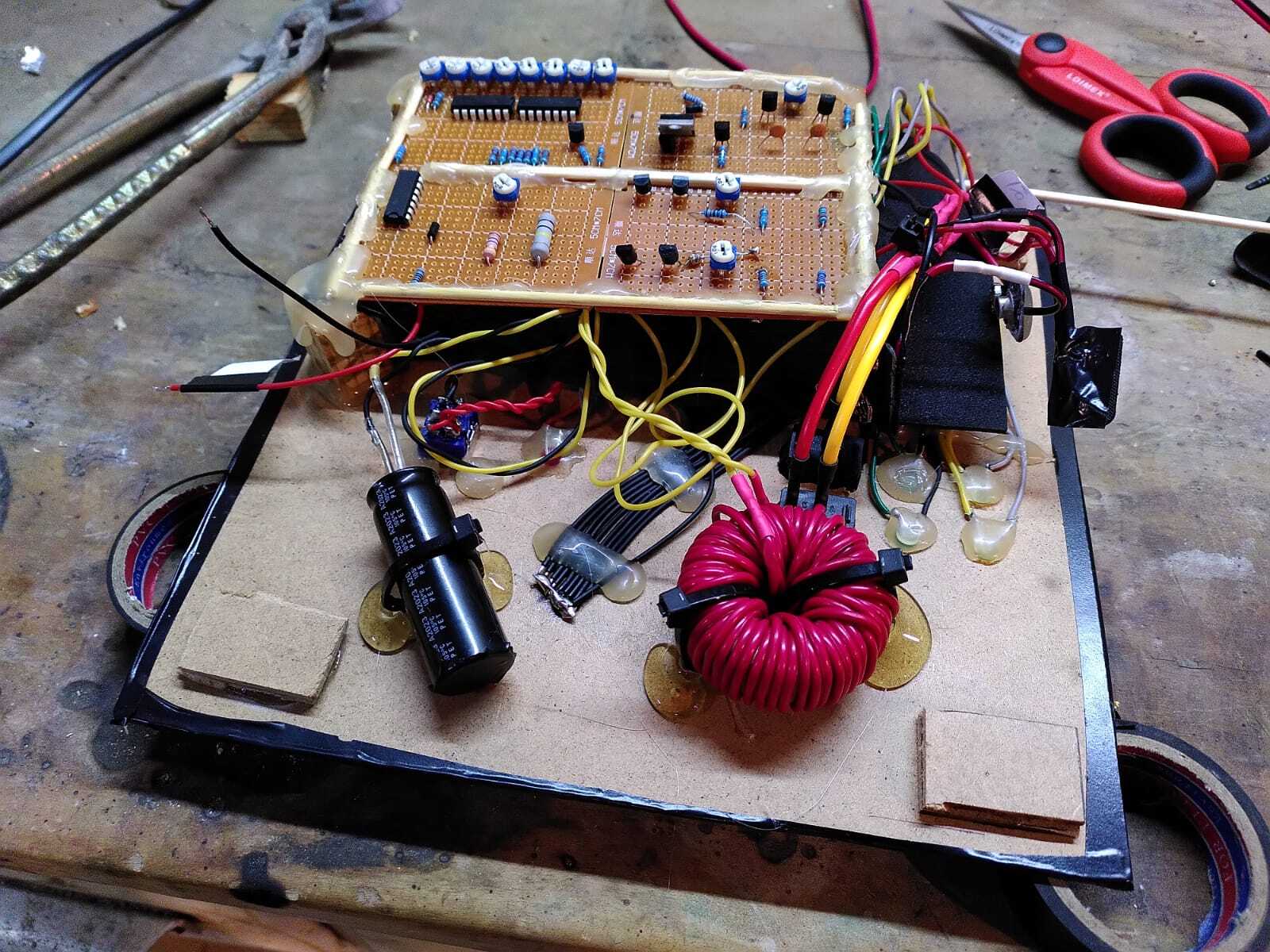

In the summer of 2022, we committed to building a more powerful and reliable system. Over eight intense days of research and prototyping (working about 14 hours a day), we studied step-up converters, designed two circuit variants, and nearly gave up on both. But in the end, we got one of them to work. Having just graduated—and from a degree not so focused on electronics—this felt like quite an achievement.

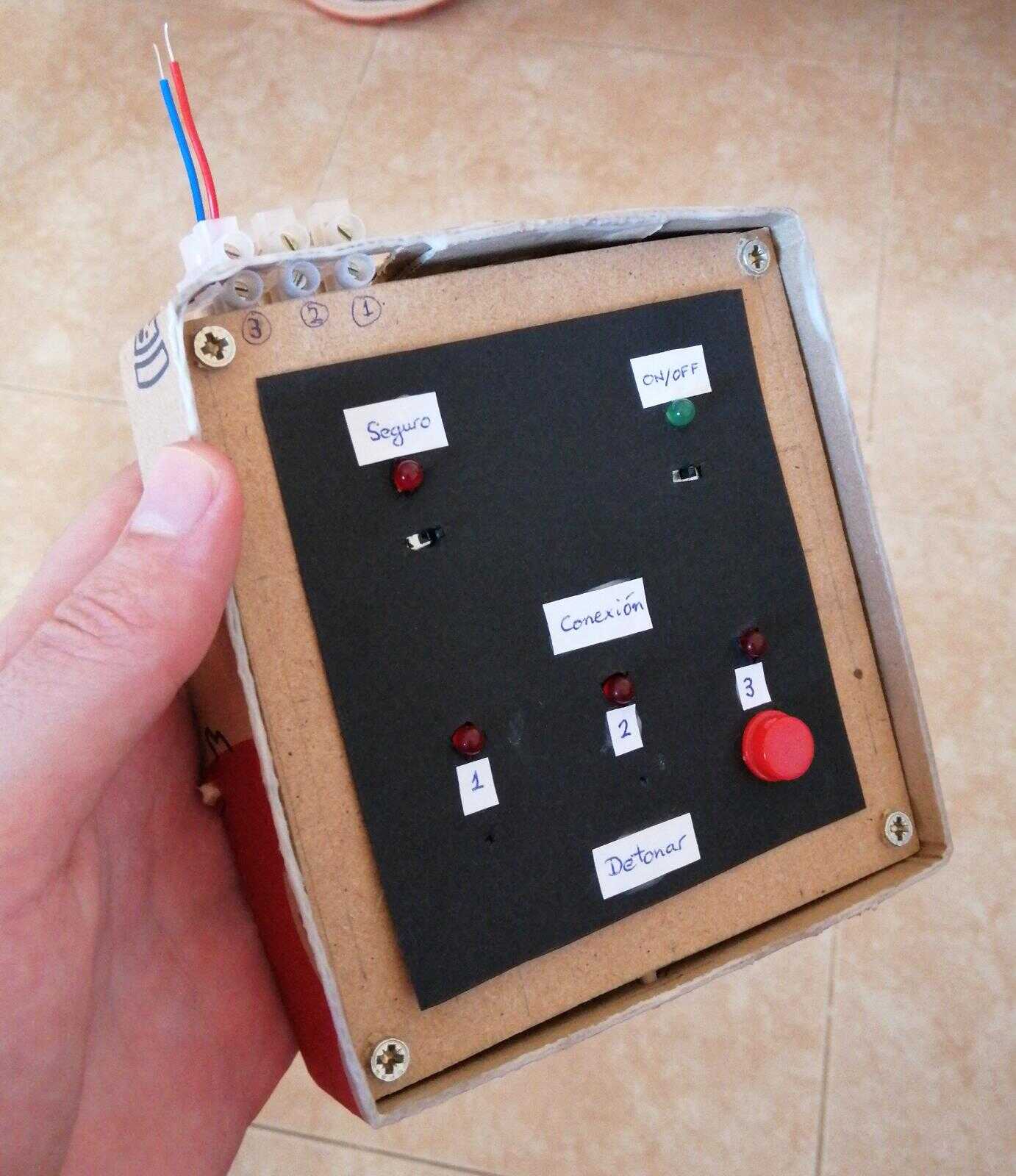

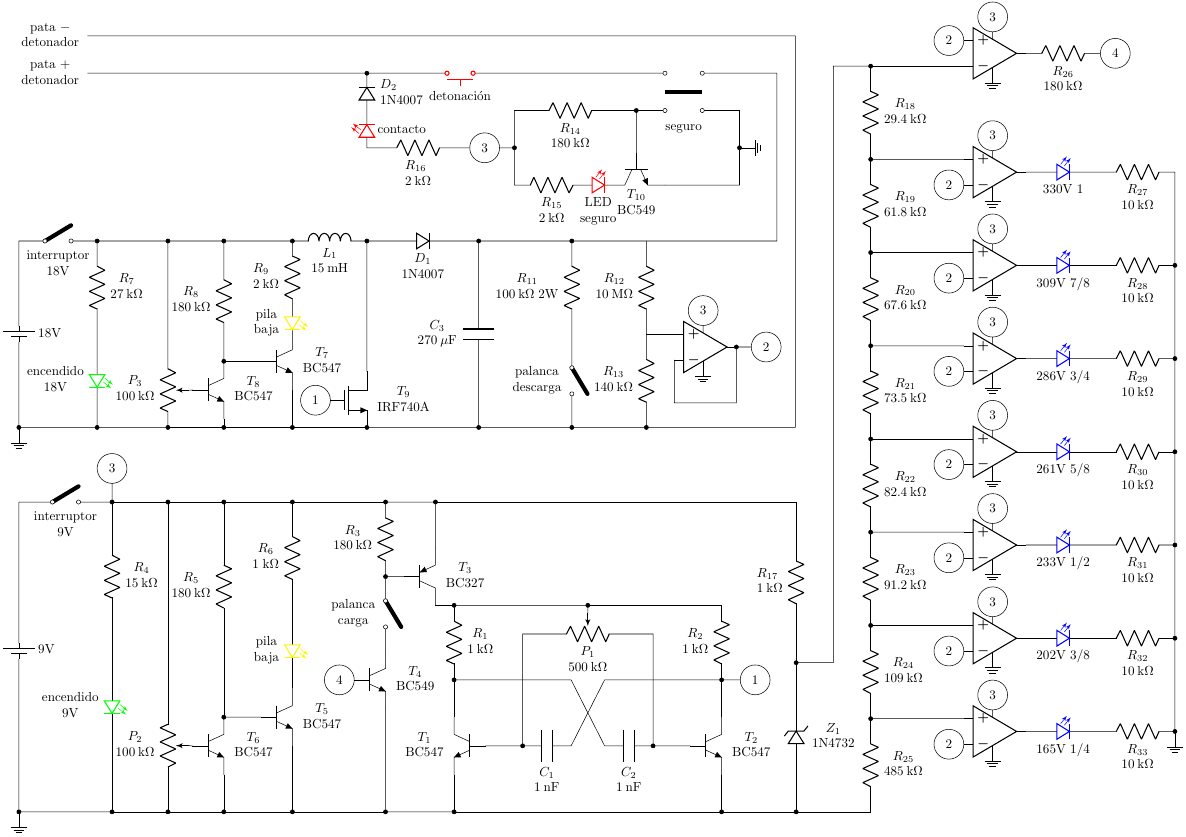

Since our physics degree only covered analog electronics, the entire system was built using discrete components—no microcontrollers yet. The most complex element was an op-amp. The result: a relatively bulky, fully analog igniter capable of boosting 18V to 330V, with LED voltage indicators, safety switches, and a large red firing button. Charging a 270 μF capacitor to 330V took about 50 seconds, it worked!—and it was portable. As a bonus, I still think it looks bad-ass.

Trying to Shrink It Down

The analog system worked great, but it wasn’t practical to transport. We aimed to shrink the design, speed up the charge time, and start integrating microcontrollers. We didn’t know much about any of those things, so there was quite a journey ahead.

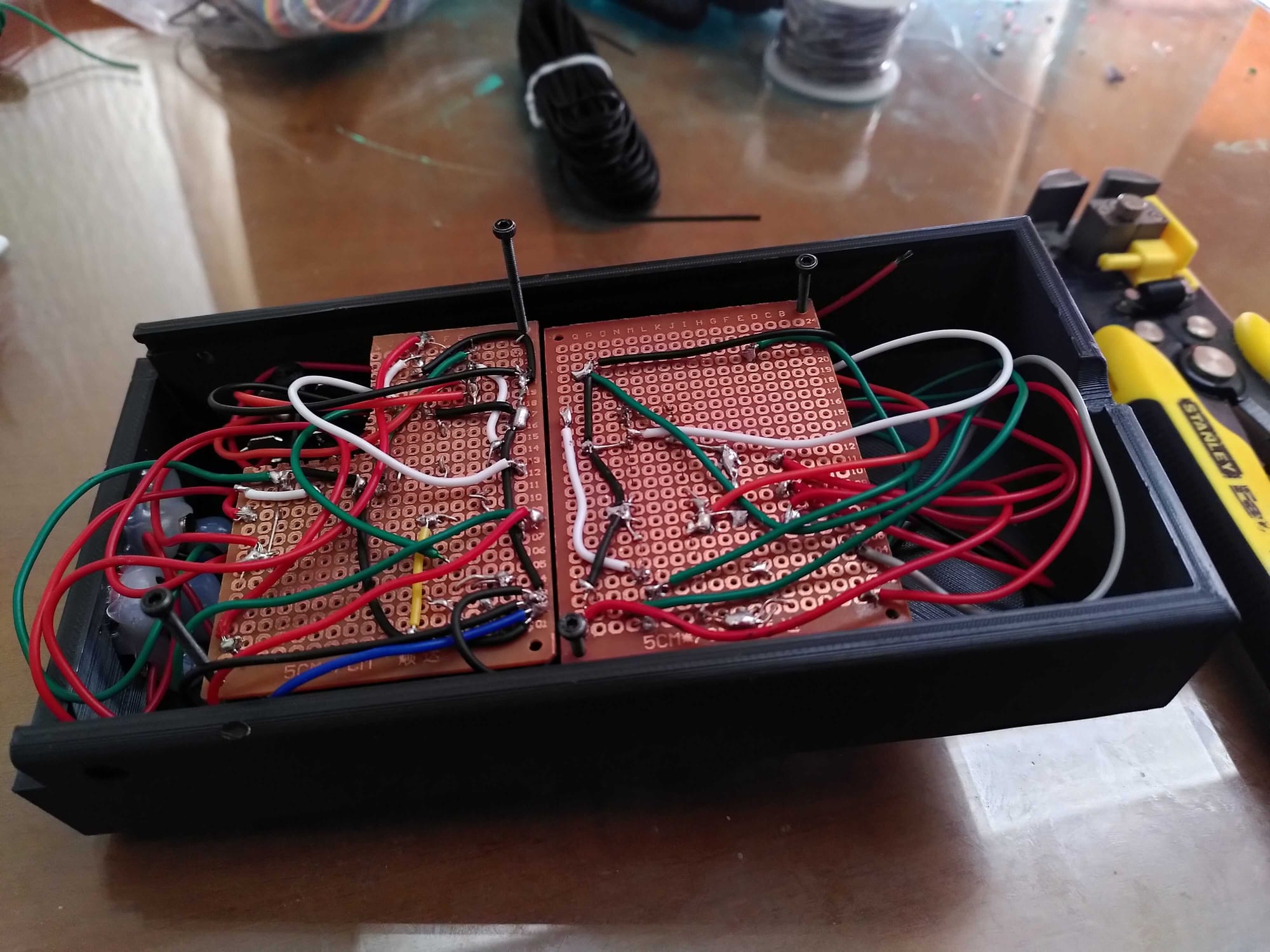

With the acquisition of my first 3D printer, some PIC16 microcontrollers, and new design ideas, we built a much smaller version. This included switching power sources—from three 9V alkaline batteries to three, small, 3.7V lithium polymer cells. Even though the input voltage was lower, with a couple of circuit improvements, we achieved a much faster charge—2.5 seconds.

However, it had some flaws as well. We pushed standard lithium batteries beyond their limits, so they burned out quickly after some use. Additionally, the internal high-voltage isolation was not very good, which led to an internal discharge that fried the low-voltage circuit during testing. Shrinking the circuit, hand-soldering all the wires, and lacking high-voltage safety experience turned out to be a dangerous combination.

From the '80s to the 2020s

In early 2023, I started working at a company that builds ultra-low-power ultrasonic wind sensors as a junior embedded systems engineer. After years of working with decades-old technology (as is often the case in academia), I was finally exposed to modern tools, methods, and workflows.

PCBs quickly became the clear path forward. Gone were the days of cutting, stripping, and soldering hundreds of wires—just thinking about it gives me chills. The availability of affordable ARM and RISC-V microcontrollers with wireless capabilities was another game-changer. Much of the analog circuitry could now be handled with some code on an ESP32.

Everything changed: hand-crafted wooden cases gave way to custom 3D-printed enclosures; tangled wires became clean, professional PCB traces; and the full-fledged physical interface was replaced with a phone app commanding the ESP32 via Bluetooth. This last step required learning to create a full app with Flutter/Dart and gaining knowledge of BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy), which eventually happened.

Of course, new problems emerged. Miniaturizing high-voltage, high-current systems introduced arc risks between closely packed components, often destroying sensitive microcontrollers. Analog components were far more robust in this regard. A simple flip of a switch could trigger internal discharges and destroy the board. Our relay-based discharge system had its own quirks too—the contacts sometimes welded shut from the intense current surges.

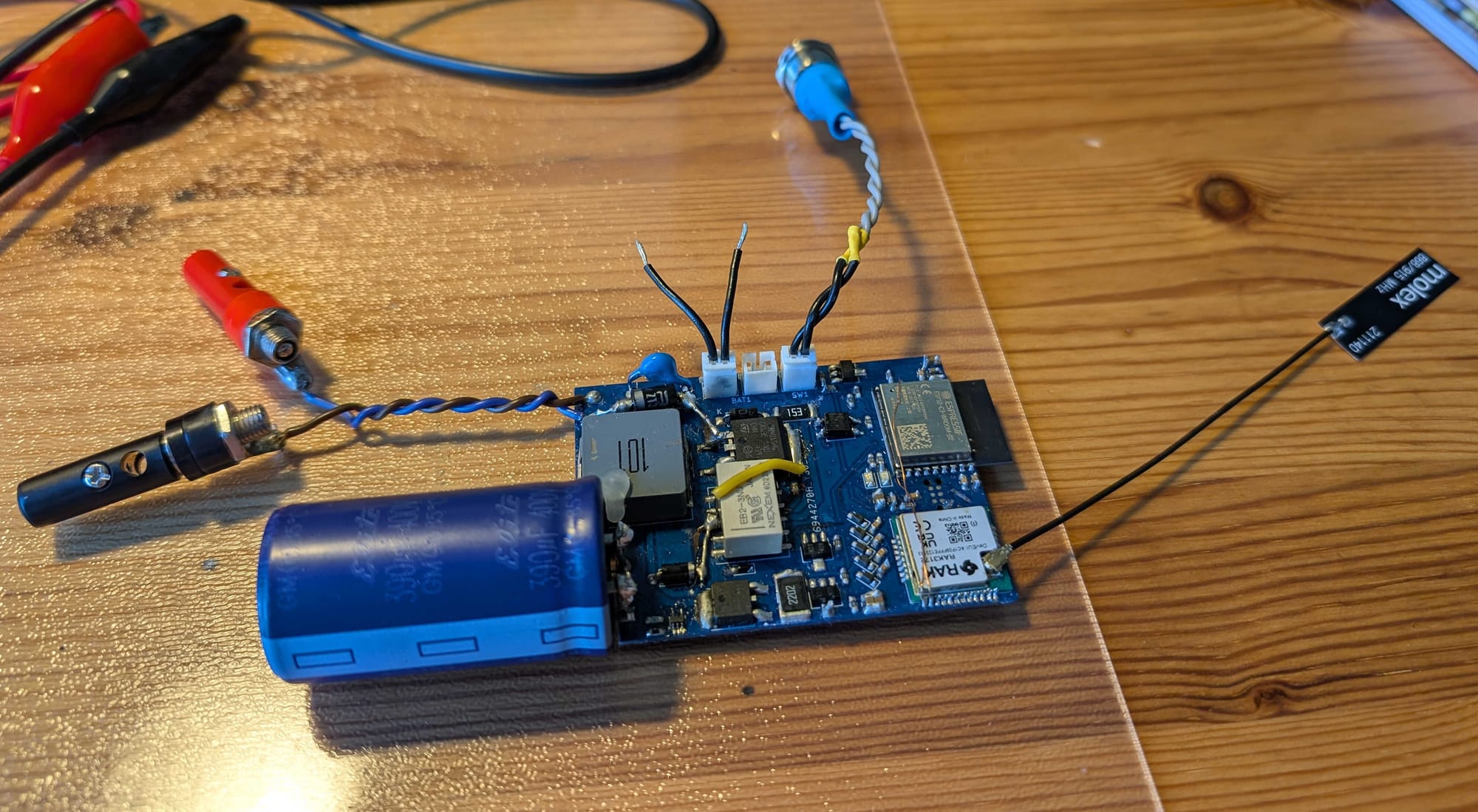

Today, the device has evolved into a reliable, portable igniter powered by a single 3.7V high-current LiPo battery. The output voltage is configurable but it has been limited to 400V to prevent damaging components—and ourselves. It can be commanded remotely via Bluetooth (up to ~150 m) or LoRa (tested up to 8 km), using a custom-built communication protocol. A pair of LEDs indicate power status and whether the high-voltage line is properly connected. The battery can be charged with a micro USB connector header on the back of the case.

The new remote control methods saved us from needing many components on the device’s front panel, eliminated the need to carry 100 meters of wire to ignite the rocket, and enabled us to use the same circuit for remotely triggering the parachute ejection. Additionally, all the things we learned and the final DC-DC boost converter circuit have already been a solid start point for some other amazing projects.

Conclusion

What began as a rough student idea turned into an invaluable learning experience in electronics, embedded systems, safety design, wireless communication, and rapid prototyping. Every fried component, every failed test, and every manually soldered joint contributed to a journey that helped shape my professional interests and skills. And it’s far from over—this was just the beginning.

This post was a very brief overview of this project, so just a few of the details and gained insights have been included. Nonetheless, it sets the context to better understand related posts in the very near future. Those will cover most things in depth and focus on transmitting our findings.